Vietnamese Ceramics and Pottery

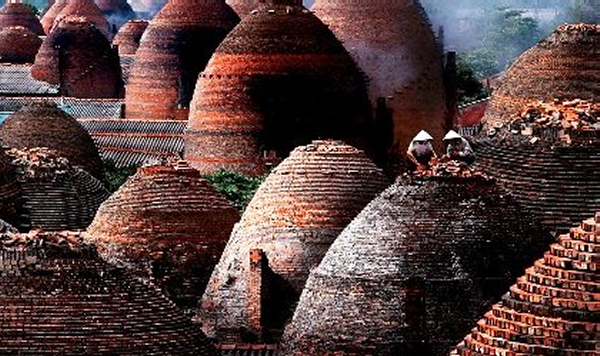

Vietnam is famous for its splendid blue de Hué porcelain. The most beautiful pieces often have a pearl with a flaming tail persued by a dragon, the symbol of the emperor. Like China, Vietnam has a long history of producing great ceramics. Susan Brownmiller wrote in the New York Times, Bat Trang is “an entire village of narrow mud lanes, artisan workshops, treadle heels, and small cross-draft kilns. Moistened pats of charcoal, straw and manure, used for fuel, were drying in rows on brick walls. Women stoically mixed and stirred vast of wet clay with their feet.”

Bat Trang Ceramic Village (Hanoi) is very old. According to historical documents, products from this village were well known as far back as the 15th century. There are many villages throughout the country that produce ceramics. Some of these villages include Phu Lang in Bac Ninh Province, Huong Canh in Vinh Phuc Province, Lo Chum in Thanh Hoa Province, Thanh Ha in Hoi An (Quang Nam Province), and Bien Hoa in Dong Nai Province.

Vietnamese ceramic is now well known in both the domestic and international markets. Traditional products include kitchen items and trays. The flower-patterned bowls of Bat Trang have been exported to Sweden, the cucumber pots to Russia, and the teapots to France. and porcelain items have been produced in Vietnam for a long time. Ceramic and porcelain products glazed by traditional methods into beautiful art are well known in Bat Trang, Dong Trieu, Thanh Ha and Haiphong. [Source: Vietnamtourism. com, Vietnam National Administration of Tourism ~]

Bui Hoai Mai is writing a book about Vietnamese ceramics. For more information contact him at: Jimmai@netnam.org.vn

Ancient Vietnamese Ceramics and Pottery

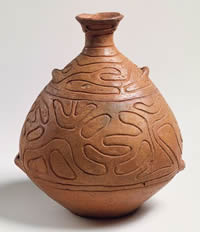

In prehistoric times, most of the designs on the surface of the ceramics were created with sticks while the products were still wet. All of the pottery products from this era had useful applications for household duties and cooking. Most of the pottery products from the Bronze Age were formed on turn tables and had diverse styles. As well as cooking utensils, there were also artistic ceramics and products for tool production. The diverse products were decorated with carved images and covered by a different colored layer of an enamel-like substance. The adornment of pottery products from this period was performed using bronze tools. [Source: Vietnamtourism. com, Vietnam National Administration of Tourism ~]

Iron Age pottery products developed in all regions of the country. These products were produced at low temperatures using somewhat rudimentary techniques. The form and ornamentation of the Iron Age pottery products was quite unique to this period. This craft developed from traditional experience, and from the influence of the Chinese. Architectural pottery, including bricks and tiles, also originated during this time and small simple statues of animals, such as pigs and oxen, were introduced. ~

In his piece “A Historical Overview of Vietnamese Ceramics,” Phan Cam Thuong wrote: “Ceramic making first appeared in Viet Nam during the country’s primitive stages of development when people gave up their wild existence to live in settled communities, and began inventing new tools and household goods. Artifacts found in archaeological sites dating back as far as the middle of the Stone Age, approximately ten thousand years ago, have been discovered at Bac Son. In the Neolithic Era, when the techniques for making stone objects had reached a high level of sophistication, ceramic products of period also began to take on an artistic character. They were no longer rudimentary jars for containing water or pots for cooking. Hoa Loc ceramic products in particular are endowed with rhythmic designs showing original geometric thinking. [Source: “A Historical Overview of Vietnamese Ceramics” by Phan Cam Thuong, Vietnam Art Books.com, VietNam Cultural Windows. Phan Cam Thuong is a researcher, art critic and writer of over 12 books in the art and art history fields. He is now a professor at the Hanoi Fine Art University and an acclaimed artist. \+\]

“The invention of pottery probably started from observation of the effect of fire on the surface of the earth. Primitive people must have noticed that on places over which fires had passed, the earth became very hard. They began to dig holes, which were baked and turned into containers for harvested rice or water. All the shapes of ceramic products likewise came into existence in the same natural way. Ancient rice bowl and dishes for instance are shaped like cupped hands the form we make with our hands to hold spring water. Jars and bottles used as containers have the same shape as fruits. \+\

“Knitted and woven products such as baskets and bamboo cages also influenced the shape of early ceramic products. Ancient jars were made by plastering knitted objects with clay before putting them into a kiln. At high temperatures, the knitted cage would burn, leaving on the ceramic jars its traces, which became small decorative motifs. Many ancient ceramic products of the Stone Age in Viet Nam bear such traces of decorative motifs. This is one possible explanation as to how the decoration on the outer surface of pottery was invented. Ceramic objects decorated with rhythmic design came into existence after the emergence of the potter’s wheel. \+\

Today we can accurately reconstruct the process of shaping and decoration employed in each of the three stage of ceramic art of the Bronze Age: Phung Nguyen (4,000 years ago), Dong Dau (3,300 years ago) and Go Mun (3,000 years ago). The processes involved in making ceramic of this period are similar to those still used in the Vietnamese countryside today. The techniques used to decorate ceramic objects of the three above-mentioned stages became the early models for decorative motifs used on the bronze objects of the Dong Son period. Sa Huynh and Dong Son ceramic in period of the Iron Age reached a remarkably high level of technical sophistication, even as precious bronze objects were beginning to come into common use. We must also add that the tools used during this period were primarily made of iron whereas the household goods were often ceramic and instruments made of bronze. Sa Huynh ceramic objects, characterized by their thickness, were generally made in the South of serve as tombs or as containers for possessions of the dead. The interaction between the shaping of bronze objects and that of ceramic is obvious; many of the ancient ceramics have the same shape as the bronze objects and vice versa. \+\

Vietnamese Ceramics and Pottery from the Period of Chinese Domination

In his piece “A Historical Overview of Vietnamese Ceramics,” Phan Cam Thuong wrote: “During the ten centuries of Chinese domination and continual struggles for independence, the Vietnamese went on producing ceramics according to their traditional methods, while trying to learn and adapt techniques of the Chinese version of the craft. [Source: “A Historical Overview of Vietnamese Ceramics” by Phan Cam Thuong, Vietnam Art Books.com, VietNam Cultural Windows. \+\]

“Ceramics excavated from Chinese tombs give evidence of the above statement. These include objects brought by Han from China, those produced by the Vietnamese, and those made by the latter according the specifications their Chinese patrons. Ceramics found in Chinese tombs from the areas stretching from Quang Ninh, Hai Duong to Bac Ninh have common shapes of the time: vessel-shaped bowls, tall cups with large mouths, tall vases called dam xoe with slender necks, large mid-sections and bell-shaped bases and terracotta house models in the architectural design of the tu dai dong duong (dwelling of four generations living together). \+\

“It is obvious that bronze objects aesthetically influenced most of these ceramics; the geometric decoration and relief motifs of the ceramic products of the period closely resemble those of bronze objects. Thanks to the high level of technical sophistication and the use of the potter’s wheel, the products were thick-walled (0.5 cm), having solid bodies with a high proportion of silicate and covered with a thin yellow or white glaze. \+\

Ceramic artifacts of the 8th, 9th and 10th centuries have also been excavated; many of these were made in the style of Tam Thai (three colors) ceramics, which flourished under the Tang Dynasty. They are covered with a transparent green glaze which accumulates in places into small lumps forming different patterns, a technique known as the “dripping spectrum” an inelegant name connected with a product considered so precious. \+\

Vietnamese Ceramics and Pottery in the Early Imperial Era

After more than ten centuries of Chinese domination, the Ly and Tran dynasties saw the reestablishment of national independence. During this period, pottery experienced splendid achievements in quality and diversity through large-scale production. Basic elements, including the form, decorations, and colored enamel, were employed t o create beautiful products. The painted decorations were simple, but incredibly attractive. Unique carving characteristics developed and various kinds of enamel were applied. [Source: Vietnamtourism. com, Vietnam National Administration of Tourism]

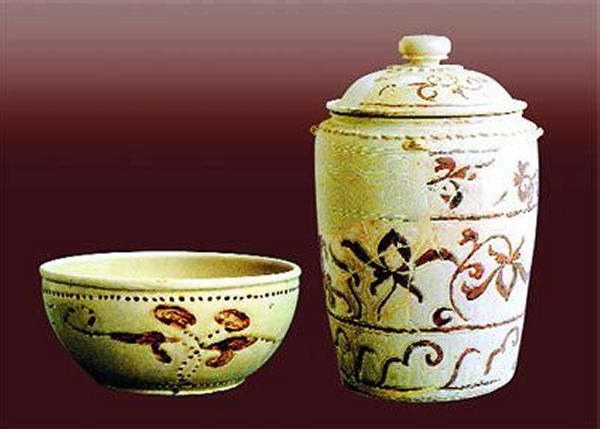

In “A Historical Overview of Vietnamese Ceramics,” Phan Cam Thuong wrote: “Vietnamese ceramics underwent an extraordinarily creative period during the Ly Dynasty (1010-1225). Craftsmen of this period undoubtedly drew inspiration from the ancient tradition of Vietnamese ceramics as well as from that of the Tang Dynasty’s Tam Thai ceramics and the Celadon porcelain tradition of the Song from China. The jade glazed ceramics of the Ly Dynasty were famous all over the Southeast and East Asian region and were prized for their beauty as far away as the Middle East. Many of the ceramics products of this period were slender in shape and covered with an emerald glaze. The glaze was produced in different shades: pale grayish green, yellow green. Light green, violet green, etc. Decorative motifs covered by the glaze remained distinct and could still be clearly seen. There were also while and black, and iron-brown glazed ceramics, all very pleasing to the eye. All of the ceramics were imbued with the same aesthetic, which underlined other artistic areas such as architecture and sculpture under the Ly Dynasty. [Source: “A Historical Overview of Vietnamese Ceramics” by Phan Cam Thuong, Vietnam Art Books.com, VietNam Cultural Windows \+\]

“Alongside the traditional ceramic centers of the Ly period in Thanh Hoa and those of the Tran Dynasty (1226-1400) in the Thang Long (now Hanoi), others were later developed in Quang Yen and Nam Dinh. According to historical documents, mandarins of this period such as Hua Vinh Kieu, Dao Tien Tri and Luu Phong Tu, who served as ambassadors to China, studied Chinese techniques of pottery making, bringing them back to Viet Nam. They taught the art to villagers in Bat Trang (Hanoi), Tho Ha (Bac Giang) and Phu Lang (Bac Ninh province). Bat Trang Village specialized in gom sac trang (white ceramics), Tho Ha in gom sac do (red ceramics) and Phu Lang gom sac vang (yellow ceramics). The white ceramics with blue motifs produced at the time differ very little from one made in Bat Trang Village today. The red pottery of Tho Ha, which was terracotta, consisted mainly of large jars and glazed coffins used in the traditional re-burying of bones of a dead body three years after the initial burial (alt for bones). While the yellow or greenish-yellow “eel skin” pottery is still produced in great quantity in Phu Lang, Tho Ha Village ceased producing it a century ago. \+\

“Terracotta products came into existence earlier than other kinds of ceramics and have continually developed throughout Viet Nam’s history, though only those of the period between the Dinh (967-980), Ly (1009-1225) and Tran (1225-1400) Dynasties reached heights of artistic excellence. Bricks were produced for paving house foundations, constructing walls and miniature towers, tiles for covering roofs, phoenix or dragon-shaped architectural decoration, and incense burners. Binh Son Tower (Vinh Phuc), 14 m high, dating back to the Tran Dynasty, is a perfect terracotta construction down to the smallest details; nothing like it has been built since. \+\

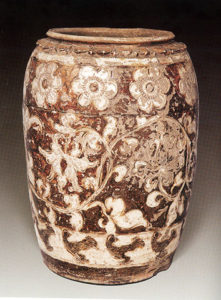

“Just as glazed ceramics were representative of the Ly period, so iron-brown pottery was of the Tran. There are two kind of latter: white background with brown motifs and brown background with white. Ceramics during the Tran period were large and simple in shape: artifacts from this period have a strong and majestic appearance, which conveys the militant spirit of the Tran Dynasty. At the end of the Tran period there also appeared gom hoa lam (white- blue glazed ceramics) and other, which used glazed of various colors between the established jade green and the blue-white glazes or between the brown and the blue-white glazes. Not until the Posterior Le (1427-1527) did white-blue glazed ceramics reach their full development. \+\

Vietnamese Ceramics and Pottery in the Late Imperial Era

Since the 15th century, ceramic started to bear white enamel with blue designs and fabrication techniques improved. Nowadays, some localities are still specialized in producing ceramics, including Bac Ninh Province, Thanh Hoa Province, Nam Dinh Province, and Hanoi.

Phan Cam Thuong wrote: “”Based on the traditional techniques of making white-blue and iron-brown glazed ceramics, Dang Huyen Thong, a pottery collector and famous craftsman of the Mac period (1527-1598), created a new kind of ceramics decorated with geometric designs and motifs in relief. The power and solemnity evoked by the designs of Dang Huyen Thong’s new pottery expressed the turmoil of the 17th and 18th centuries: ceramic art together with other handicraft developed alongside the changing village and urban centers in the context of a country divided by an internal war which lasted for two hundred years. [Source: “A Historical Overview of Vietnamese Ceramics” by Phan Cam Thuong, Vietnam Art Books.com, VietNam Cultural Windows \+\]

“After transferring its capital to Hue, the Nguyen Dynasty (1802-1945) also paid attention to the ceramic craft for the service of the court and daily life. New centers of porcelain and ceramic production such as Mong Cai and Dong Nai began to emerge alongside long-established old centers and kilns. The porcelain trade under Qing Dynasty in China and the Nguyen in Viet Nam prospered. Many courtiers of Asia Minor and Central Asian imported Vietnamese ceramics. \+\

“Nowadays modern ceramics are based on traditional techniques of ceramics making which have operated for hundreds of years. What on the past was a glorious craft requiring great skill is today another developing branch of industry. Beside the ancient centers, which are still operating and continue using traditional methods, many new and old communities have begun using imported techniques, such as casting, the use of chemical glazes, and firing in gas or electric kilns. The shapes and decorations of many products now follow international aesthetic tastes. Traditional ceramics, however, retain their own value, an ancient tree amidst an industrial forest. \+\

Bat Trang Markets Its1,000-Year-Old Ceramic

Associated Press reported from Bat Trang: “Nguyen Trong Hung smoothes his weathered hands over a 1.5-metre-tall porcelain vase spinning hypnotically on a potter’s wheel. Years of practice make his movements look effortless as he creates a flawless work based on traditions passed down through generations. Bat Trang, a village on the Red River just outside Hanoi, has been producing ceramics and pottery for 1,000 years and is known throughout Vietnam for its quality and innovative wares. [Source: Associated Press, December 5, 2004 <>]

“And, with communist Vietnam opening its doors to a market economy, artisans like Hung, who were once forced by the government to work for pennies, are now fledgling entrepreneurs dreaming that their village will someday rival France’s famed Limoges porcelain region. “All of the ceramic craftsmen in this village are very proud of the craft we inherited 1,000 years ago from our ancestors,” says Hung, who began learning the trade at age five. “We hope with this project, more people in the world would know about Bat Trang ceramics and that would help to raise the sale of our products to a new height.” <>

“Hung’s family and 26 others from the village of 400 ceramics producers have joined a pilot project – the Bat Trang Porcelain and Ceramics Association – that began promoting their wares in November. They hope that with some expertise from the Mekong Private Sector Development Facility – which is managed by a branch of the World Bank and which has pledged $150,000 over two years for a Web site, a trading center and improved marketing – they can begin selling directly to department stores abroad. <>

In 2003 “the village, which employs an estimated 30,000 people, exported about $23 million US worth of ceramics. It’s a number that project head Len Cordiner hopes to double over the next three years. “I think it’s ambitious, but it’s very doable,” Cordiner says. “To become a household name will take 10 or 20 years, but we may – at least I’m hoping – do reasonably well in the wholesale and retail trade.” There are hundreds of craft villages scattered across Vietnam with skilled artisans making everything from rattan and wrought iron furniture to silks and lacquerware. But Bat Trang is special. <>

“Its history traces back to a site outside the ancient capital of Hoa Lu in northern Vietnam where pottery artisans once gathered. In 1010, the craftsmen moved with the capital to Hanoi, and relics of Bat Trang pottery and ceramics have been unearthed at the site of an ancient citadel there – evidence that even Vietnam’s royal families used wares created by the villagers’ ancestors. Bat Trang products have been found in shipwrecks across Southeast Asia and exhibited in museums worldwide. Foreign experts were surprised to find that some of Bat Trang’s ancient techniques were more modern and sophisticated than expected, similar to relics found in Japan and China, says Duong Trung Quoc, a Vietnamese historian. “The cultural value of the product is its economic strength,” he says. “It helps the foreigners understand Vietnam, and the quality of the product will help them to believe in other products made by Vietnam.” <>

“While still making each item by hand – right down to the intricate scenes and patterns etched on the porcelain – some families are innovating. Three years ago, Hung switched from a coal-fired kiln to one powered by natural gas. It’s 50 percent more expensive, but his pieces are more evenly heated and there is no more messy coal dust or time lost hauling in fuel. Only 30 percent of his output is exported now, but Hung’s family earns about $6,370 annually, far above the national average of about $420 a year and a big change from the poverty and hardship of two decades ago. After the Vietnam War ended in 1975, the communists forced Bat Trang’s villagers to produce bowls and plates that Hung says paid only pennies for a day’s work, enough to buy just over three pounds of rice. It was when Vietnam started opening up the economy and promoting private businesses that the village began making money. Today ceramic-filled shops line both sides of the street leading into the village and a large outdoor market booms near the river. <>

“Cordiner hopes to eventually begin tours to Bat Trang and to create a similar niche like Les Artisans d’Angkor has done in Siem Reap, Cambodia, where craftsmen make lucrative, high-quality souvenirs. “We’re leveraging the history of the town and the history of ceramic production, which are closely tied,” he says. “It’s visible, tangible evidence of history.” <>

15th Century Vietnamese Dish

Describing a 15th–16th century stoneware dish with underglaze cobalt blue decoration, Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Though real elephants are large and heavy, the one pictured at the center of this plate seems to float among Chinese-style “wish-granting” clouds. From very early times, the Vietnamese had been influenced by the beliefs and art styles of their large neighbor, China. By the fifteenth century, Chinese blue-and-white ware was famous worldwide and Vietnamese potters had also begun to excel in this borrowed technique in which the designs are painted in cobalt blue on the white porcelain surface. The surface is then coated with a transparent glaze before firing. [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York ><]

Although the clouds and the blue-and-white underglaze technique are derived from China, the way the elephant is portrayed is entirely different. In India, the elephant was an ancient symbol of royalty. In China, ele- phants were imported to add to the grandeur of imperial ceremonies and processions. In Vietnam, elephants were domesticated and were essential vehicles for transporting people and goods. Perhaps that is why the deco- rator of this dish painted the elephant with such familiarity, humor, and affection. The elephant turns as if to admire its loose hide, which is patterned with dot clusters resembling flowers. The curves of its soft chin and large eyes (with eyelashes) create a smiling expression. The rounded outlines of the cloud patterns and the elephant’s tusk, trunk, and body fit harmoniously inside the central circle of the dish. ><

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Vietnamtourism. com, Vietnam National Administration of Tourism, CIA World Factbook, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, Fox News and various websites, books and other publications identified in the text.

© 2008 Jeffrey Hays

Last updated May 2014

Source: http://factsanddetails.com/southeast-asia/Vietnam/sub5_9e/entry-3428.html#chapter-11

Ceramics and pottery are used interchangeably ay times, which is not a problem as there is little difference among the words. The words both refer to an art form which shapes and molds clay. However, technically speaking, the word ceramics is a more general term and it includes the term pottery.

Ceramics and pottery are used interchangeably ay times, which is not a problem as there is little difference among the words. The words both refer to an art form which shapes and molds clay. However, technically speaking, the word ceramics is a more general term and it includes the term pottery.

Canh Thinh bronze drum was cast in the 8th year of the Canh Thinh reign, Tay Son Dynasty (1800).

Canh Thinh bronze drum was cast in the 8th year of the Canh Thinh reign, Tay Son Dynasty (1800).